Rank and Name, Private Edward Jackson McCain.

Unit/Placed in, 4th Chemical Company, Aviation, United States Army Air Force.

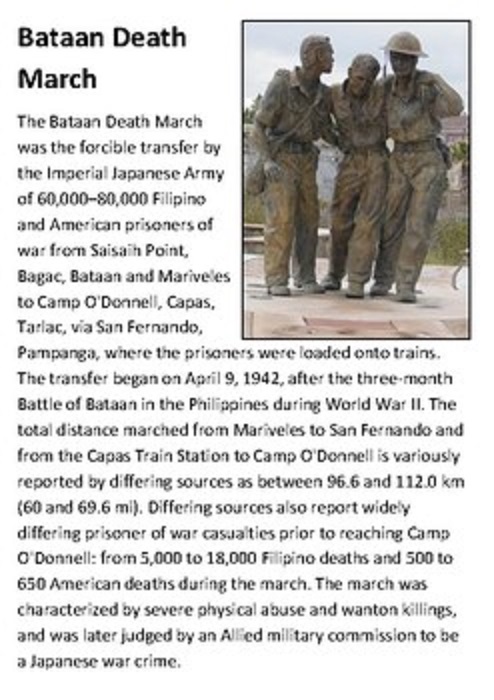

Bataan Death March (more info below).

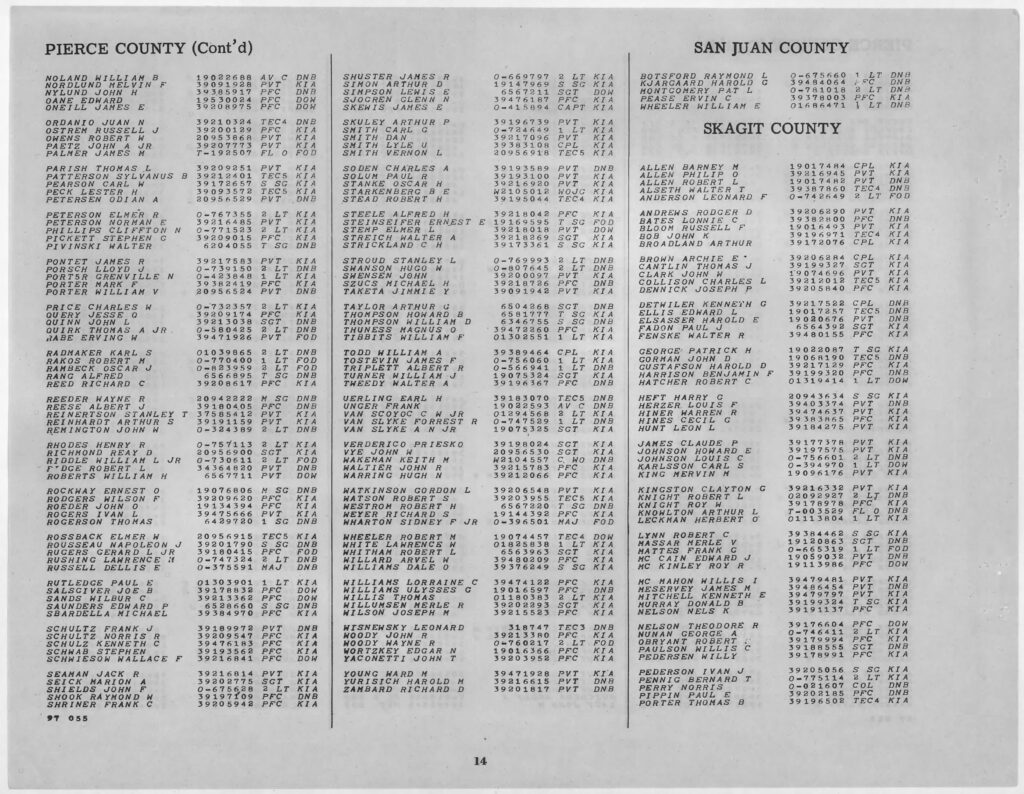

Edward is born approx. on 15 December 1919 in Mount Vernon, Skagit County, Washington.

Father, Levi Emerson McCain.

Mother, Pauline (Test) McCain.

Sister(s), Elvira E. McCain.

Brother(s), David Brooks McCain.

Edward enlisted the service in Washington with service number # 19059032.

Edward died in General Hospital #1, because of the seriousness of his illness/injuries he was not sent on the Bataan Death March as he was unable to walk. he died on 16 June 1942, he is honored with a POW Medal, Good Combat Ribbon, Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal, WW II Victory Medal.

General Hospital Number 1 – December 23, 1941 to June 29, 1942. General Hospital Number 1 was organized per verbal orders of the Commanding General, U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, on December 23rd, 1941. On this date the hospital was opened at Camp Limay, Bataan. The greater part of the equipment and supplies for a 1000 bed general hospital had been stored at this camp some months previously in accordance with War plans. Additional supplies including some food stores, were trucked from the Station Hospital, Fort William McKinley, and the disbanding Manila Hospital Center by Personnel of Hospital Number 1 between December 23, 1941, and January 1st, 1942, when Manila fell to the Japanese.

Edward is buried/mentioned at Manila American Cemetery and Memorial Manila, Metro Manila, National Capital Region, Philippines.

Thanks to,

https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/GHKR-ZD9

Jean Louis Vijgen, ww2-Pacific.com ww2-europe.com

Air Force Info, Rolland Swank.

ABMC Website, https://abmc.gov

Marines Info, https://missingmarines.com/ Geoffrey Roecker

Seabees History Bob Smith https://seabeehf.org/

Navy Info, http://navylog.navymemorial.org

POW Info, http://www.mansell.com Dwight Rider and Wes injerd.

Philippine Info, http://www.philippine-scouts.org/ Robert Capistrano

Navy Seal Memorial, http://www.navysealmemorials.com

Family Info, https://www.familysearch.org

WW2 Info, https://www.pacificwrecks.com/

Medals Info, https://www.honorstates.org

Medals Forum, https://www.usmilitariaforum.com/

Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com

Tank Destroyers, http://www.bensavelkoul.nl/

WordPress en/of Wooncommerce oplossingen, https://www.siteklusjes.nl/

Military Recovery, https://www.dpaa.mil/

DEATH MARCH

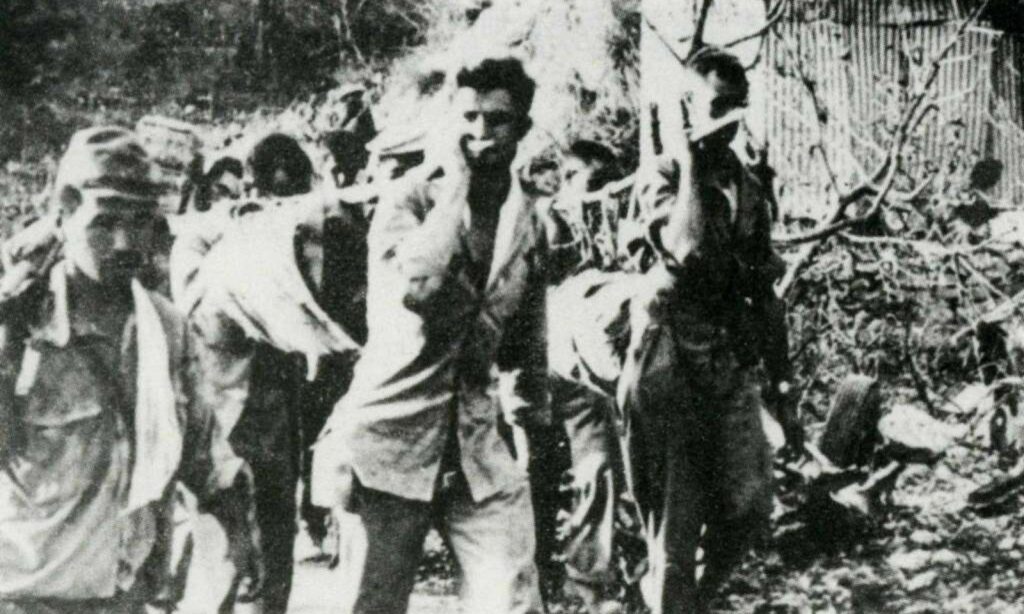

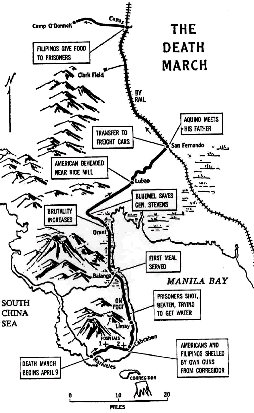

Following the surrender of Bataan on April 9, 1942, to the Imperial Japanese Army, prisoners were massed in Mariveles and Bagac town.

As the defeated defenders were massed in preparation for the march, they were ordered to turn over their possessions.

Word quickly spread among the prisoners to conceal or destroy any Japanese money or mementos, as the captors assumed it had been stolen from dead Japanese soldiers.

Prisoners started out from Mariveles on April 10, and Bagac on April 11, converging in Pilar, Bataan, and heading north to the San Fernando railhead.[3] At the beginning of capture there were rare instances of kindness by Japanese officers and those Japanese soldiers who spoke English, such as sharing of food and cigarettes and permitting person-al possessions to be kept. This was fast followed by unrelenting brutality, theft, and even knocking men’s teeth out for gold fillings, as the common Japanese soldier had also suf-fered in the Battle for Bataan and had nothing but disgust and hatred for his “captives” (Japan did not recognize these people as POWs).[4] The first atrocity—attributed to Colonel Masanobu Tsuji—occurred when approximately 350 to 400 Filipino officers and NCOs under his supervision were summarily executed in the Pantingan River massacre after they had surrendered. Tsuji—acting against General Homma’s wishes that the pris-oners be transferred peacefully—had issued clandestine orders to Japanese officers to summarily execute all American “captives.”Though some Japanese officers ignored the orders, others were receptive to the idea of murdering POWs.[12]

During the march, prisoners received little food or water, and many died.[2][13][14] Prisoners were subjected to severe physical abuse, including being beaten and tortured. On the march, the “sun treatment” was a common form of torture. Prisoners were forced to sit in sweltering direct sunlight, without helmets or other head covering. Any-one who asked for water was shot dead. Some men were told to strip naked or sit within sight of fresh, cool water.[8] Trucks drove over some of those who fell or succumbed to fatigue, and “cleanup crews” put to death those too weak to continue, though some trucks picked up some of those too fatigued to continue. Some marchers were randomly stabbed by bayonets or beaten. The Death March was later judged by an Allied military commis-sion to be a Japanese war crime.

Once the surviving prisoners arrived in Balanga, the overcrowded conditions and poor hygiene caused dysentery and other diseases to spread rapidly. The Japanese did not provide the prisoners with medical care, so U.S. medical personnel tended to the sick and wounded with few or no supplies.[13] Upon arrival at the San Fernando railhead, prison-ers were stuffed into sweltering, brutally hot metal box cars for the one-hour trip to Ca-pas, in 43 °C (110 °F) heat. At least 100 prisoners were pushed into each of the trains’ unventilated boxcars. The trains had no sanitation facilities, and disease continued to take a heavy toll on the prisoners.

Upon arrival at the Capas train station, they were forced to walk the final 14 km (9 mi) to Camp O’Donnell. Even after arriving at Camp O’Donnell, the survivors of the march continued to die at rates of up to several hundred per day, which amounted to a death toll of as many as 20,000 Filipino and American deaths. Most of the dead were buried in mass graves that the Japanese had dug behind the barbed wire surrounding the com-pound. Of the estimated 80,000 POWs at the march, only 54,000 made it to Camp O’Donnell.

The total distance of the march from Mariveles to San Fernando and from Capas to Camp O’Donnell (which ultimately became the U.S. Naval Radio Transmitter Facility in Capas, Tarlac; 1962-1989) is variously reported by differing sources as between 96.6 and 112.0 km (60 and 69.6 mi).

Thanks To Wikipedia